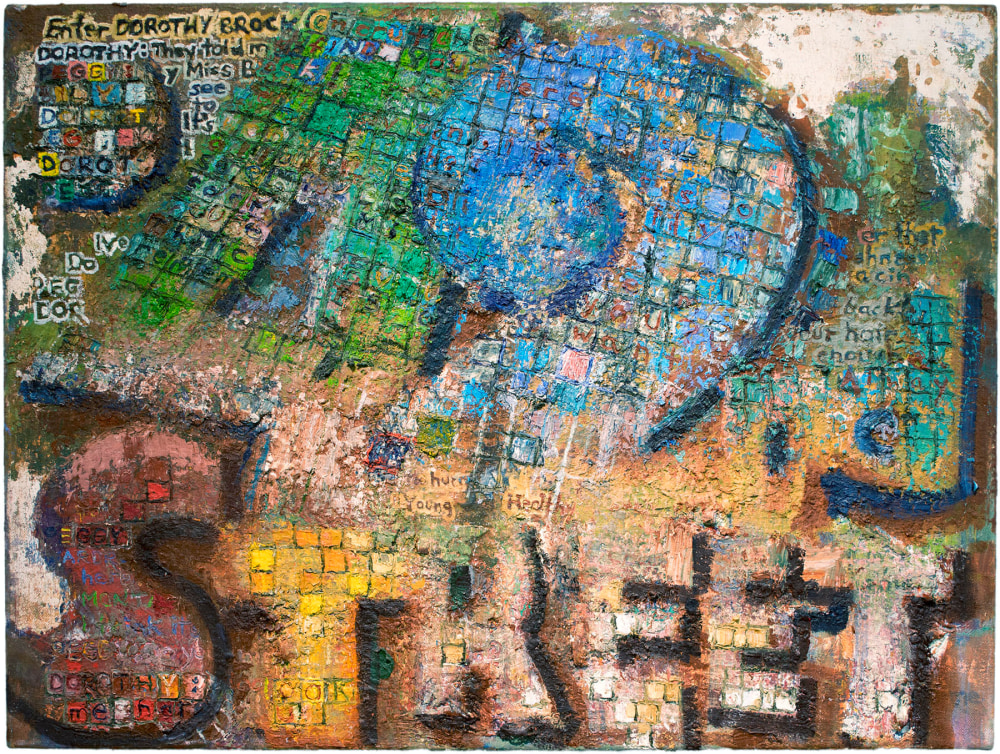

John Lees, 42nd Street (Tesserae), 2015. Courtesy of Betty Cuningham Gallery

In 1906 the critic Philip Hale remarked that he perceived a “fine insanity” in the work of Marsden Hartley, by which the artist took him to mean “a strong insistence upon the personal interpretations of the subjects chosen.” While Marsden might not be the first name to come to mind in viewing John Lees’ fourth solo exhibition at Betty Cuningham, Lees does harness his unequivocal mastery of paint into building images that speak of a similar, profound commitment to inner reflection.

A sense of gravitas pervades these somber works. The paint itself is what is initially so striking and so momentous, inexorably annexing the viewer’s attention through its almost unbearable beauty of crusty and pitted layers of rich pigment. Clown in a Frame speaks this exalted language of densely textured paint- the language of Georges Rouault- without reservation, even absconding with Rouault’s decorative framing. Yet the source of the sentiment informing the subject transcends easy reference to the French master and is deeply personal for Lees. Lees was the clown. Lees was Dilly Dally (the puppet from the Howdy Doody show of the 1950s). The relationship between subject and artist is direct. These two characters, that of the Dilly Dally and the clown, are primary sources of identification for the artist in his childhood and adolescence. Resurfacing in his work over the years, they have become an integral part of what Lees refers to as “purging” himself of his past. Clown in a Frame and Dilly Dally are images born of memory, densely processed through years of labor in the studio. However, the note that Lees seeks to sound is, in the end, less about memory, less about Time recollected, but rather about the ongoing effect of Time, the process of aging. The clown and Dilly Dally show severe signs of the wear and tear of Time passing—especially in the mournful watercolor Ghost of Dilly Dally, 2007, where the image of Dilly Dally is especially haunting, the surface of the paper barely retaining a few traces of the hapless puppet who has been literally effaced.

These images, are, however, but an introduction to Lees’ most powerful treatise on aging, the portraits of his father. First evoked in a fine series of tooled drawings on the first floor of the gallery, the father assumes true iconic form downstairs in five fiercely moving paintings in which the remorselessness of Time gnaws and gnaws at this simple fellow sitting in his armchair with his Lucky Strikes and drink. Four of those images are quite small and so tactile that if this was a museum show there would be a barrier keeping them at at safe distance from the public. The persistent process of toil that produces these savage, mottled surfaces could, in a lesser artist’s hands, suffocate the image. Indeed, even in the work of Frank Auerbach sometimes the paint itself has a tendency to dominate and overpower the image, reading as paint before it reads as form. Here, as in Rouault, the endless layering is constantly felt in service of form (It is of considerable interest that Lees cites Rouault again and again as “the door” that he found and opened and led to his becoming an artist). Lees proves himself skillful at resuscitating his work time and time again over the years, often scraping and scouring with chemical removers until the surface reawakens. For to Lees, it is all about the paint. “If the paint does not go bumpity bumpity, what’s the point?”This pitiless working of the paint is best witnessed in Man Sitting in an Armchair (Red Dog), 2008-2015, where the greater part of the back plane of the picture has been scraped entirely off. The most evocative of all these smaller portraits of the artist’s father is Man Sitting in an Armchair, 1971; 2013-14. Here the head is processed completely out of focus, dissolving into the stream of passing time, the red dot of the cigarette package glowing like a dying ember.

Dominating the lower gallery is the largest painting of the exhibition, Man Sitting in an Armchair, 2008-2015. Here, again, the focus of the picture seems not so much about a memory of a man, a father, but rather about the diffusion of the form through aging. Miraculously, as the edges of the forms dissolve, the forms themselves seem heightened and fulfilled. Indeed, the forms assume a feeling of inherent necessity in terms of the pictorial structure, as opposed to the diffuse forms that often may actually weaken the structure of an Impressionist work. The content of Lees’ portraits is also somehow mysteriously sustained, despite the vagueness, despite the exaggerated or caricatured features. One still feels the keenness of his pain in confronting his feelings of his father and the need to purge those feelings is palpable.

Perhaps the most curious work of the entire exhibition is In the Park, 2008. A figure of an old man with a cane is seemingly morphing into a man playing a saxophone. The fractured image is riveting. What is the meaning of this? Lees cites the old man as a self portrait, the image as a refection on the inevitable aging process, mixed with his love of jazz. He feels that his pictures, at their best, touch on the big sound of saxophonist Ben Webster: “big sound, big tone, but played out in paint.” Again, the working of the paint itself in this mysterious work is ravishing, every quadrant of the canvas alive and rich. An orange cat tightens the right foreground, its paws almost fixed into the frame. A tiny black glyph becomes another cat, a white limbed runner dashes in from the right with a radiant yellow shoe and a spectral palm gloomily closes the top left which makes the completely scraped opposing right corner breathe into infinity.

The theme of aging continues with the series 42nd Street, pieces dating from 2014 and 2015, and not bearing the full burden of Lees’ incorrigible work process. Still, the play of surface and color powerfully and inventively reverberate and the text of the actual 1933 film of the same title, painstakingly scripted throughout, adds a poignancy to these more brazen images. The mood is significantly lightened, however, and the gravitas reduced to an understanding of the cinematic scene introduced in the text.

There is a reason for this lightening of tone. The 42nd Street series has its place in Lees’ vision, heralding in a new season of more immediate and hopeful, less troubled and inflicted work. After a long, long and often dark road, confronting and wrestling with his personal demons and trying to reconcile himself to his past, Lees speaks of wanting to “pay attention to life here now” and purge himself of all the unpleasant associations he has with his youth. He wants to, in a word, move on. The new wave of images will literally be born out of the older images, the artist incapable of starting on a virgin surface. Rather, he can already visualize transfiguring existing, unfinished works into new configurations- figures morphing into trees, trees into figures, cats into birds. Through a new lens, Lees is now willfully seeking to repudiate the weight of previous themes or subjects.

And that shall indeed be a much anticipated development for those of us who have enthusiastically followed Lees’ journey thus far, through the glass, darkly.